A Denver judge jailed a man for 12 days for failing to pay child support, but she ignored procedural requirements and safeguards to hold someone in contempt, the state Court of Appeals has ruled.

District Court Judge Nikea T. Bland sentenced Rory Fitzgerald Carpenter to jail in January 2022 after a hearing in which Carpenter admitted he had failed to make all required payments stemming from his divorce case.

There is two types of consequences a judge can impose for contempt: remedial sanctions, which compel someone to comply by performing an action, and punitive sanctions, which punish behavior “offending the authority and dignity of the court”.

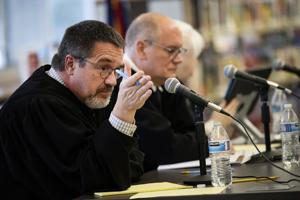

A three-judge Court of Appeals panel found that Bland never explicitly described the type of punishment she was imposing on Carpenter. If this was a fix, there was no indication that the incarceration would end if Carpenter corrected his behavior. If it was punitive, there were multiple errors in the imposition of the punishment.

“First, the father was denied his right to counsel,” Judge Ted C. Tow III wrote. in the opinion of the panel of July 13. “Second, the court did not find that the continued non-payment was offensive to the authority and dignity of the court.”

Previously, Bland had charged Carpenter with both punitive and restorative contempt in March 2021 for his failure to pay child support and other obligations. She imposed six days in prison on him and also ordered him to pay monthly installments. Bland set a review for January 2022 to “monitor compliance” with Carpenter’s payments.

Shortly before the hearing, Bland found that although Carpenter had not paid all of his debt to his ex-wife, he appeared to be complying with the contempt order. But at the hearing itself, Carpenter acknowledged that he had once again fallen behind on his payments. Bland then imprisoned him for 12 days.

Carpenter, representing himself, argued before the Court of Appeal that Bland failed to follow proper contempt procedure.

“The Appellant’s contention is that due process is always required,” he wrote, “and should be afforded him, especially since the penalties, if found guilty, include the possibility of imprisonment.”

Carpenter’s ex-wife countered that the hearing was “just a continuation” of previous proceedings and that no further precautions were required.

The Court of Appeal disagreed. While Bland wanted the penalty to be corrective—to bring Carpenter into compliance with her child support obligations—she never determined whether Carpenter had the ability to pay as of January 2022. Also, it was unclear that the incarceration would end if Carpenter made payments after all.

On the other hand, while the sanction was meant to be punitive, Bland did not explain how Carpenter’s failure to pay at the time was offensive to the authority and dignity of the court. Similarly, Carpenter did not have an attorney, as required by the rules, nor did Bland advise him of his right to have another judge conduct the hearing.

“A person charged with punitive contempt is entitled to certain due procedural protections before the court can impose such penalties,” Tow wrote. “The district court did not provide these protections to the father here.”

The court quashed the contempt order.